PACT: A broad-based approach to phonological intervention - theoretical background and evidence

- Details

- Created: Tuesday, 15 November 2011 15:18

- Updated on Wednesday, 04 February 2015 11:59

What's in a name?

Since 1998 when the first version of this article was written, the broad-based phonological therapy described here has acquired a name! We called it PACT. 'PACT' is an acronym for 'parents and children together', and reflects the family-focus of the approach (Bowen & Cupples, 1998a, 1998b). There have also been several more publications about the approach since 1998: see PACT Publications.

Parents and Children Together: PACT

Theoretical Background and Evidence

Introduction

The terms ‘developmental phonological disorders’ and 'phonological disorder' broadly denote a group of linguistic disorders in children, manifested by the use of abnormal patterns in the spoken medium of language, impairing their general intelligibility.

Our profession’s understanding of these disorders has seen remarkable changes since Ingram’s (1976) seminal work on natural phonology (Stampe, 1979) in the mid-1970’s.

- First, due to the influence of linguists and speech-language pathologists working in the area of clinical phonology (Ball & Kent, 1997), the disorder is seen, nowadays, as both developmental and psycholinguistic (Chiat & Hunt, 1993; Locke, 1994; Stackhouse & Wells, 1993; Vihman, 1996).

- Second, there is increasing recognition of the key role primary care-givers can play in the therapeutic process (Bowen & Cupples, 1998; Crago, 1992; Flynn & Lancaster, 1996; McWilliams, Winton & Crais, 1996).

- And third, there is an insistent call for further research into treatment efficacy (e.g., Baker van Doorn & Reed, 1996; Fey, 1992; Gierut, 1998; Grunwell, 1995; Pollock, 1994; Sommers, Logsdon & Wright, 1992).

Phonological therapy

Stoel-Gammon and Dunn (1985, p. 168) provided a neat summation of the characteristics of phonological therapy, saying that it:

- is based on the systematic nature of phonology;

- is characterised by conceptual, rather than motoric, activities; and,

- has generalisation as its ultimate goal.

Similarly, Fey (1992) stated that: phonological therapy approaches are designed to nurture the child’s system rather than simply to teach new sounds (p.277).

Meanwhile, Grunwell (1988) had captured the essence of what taking a ‘phonological’ approach to intervention for developmental phonological disorders means when she wrote that, The defining characteristic of phonological therapy is that it is ‘in the mind’.

Of course phonological therapy can take a number of forms, and the clinician is faced with choosing from an increasing array of theories, approaches, procedures and activities. For example, the discerning practitioner might be encouraged by the research literature to apply the phonological process approach based on natural phonology theory and using minimal meaningful contrast activities (Weiner, 1981a; Saben & Costello-Ingham, 1991); or the maximal opposition treatment arising from standard generative phonology theory (Gierut, 1992); or the popular, effective and largely atheoretical cycles therapy approach (Hodson, 1994); or Flynn and Lancaster’s (1996) eclectic combination of auditory input therapy plus minimal contrast and articulation therapy; or indeed the approach suggested by Grunwell (1995).

Although it has been in the development stages for around a decade, Bowen’s (1996) approach is a relative newcomer to the clinical phonology scene, and the first phonological therapy to be tested with treated and untreated groups of children. The model is founded on sound theoretical principles while being both broad-based and eclectic.

Kamhi (1992) used the term ‘broad-based’ when he argued the need for a treatment methodology that had some explanatory value, stating that: "Such models are consistent with assessment procedures that are comprehensive in nature and treatment procedures that focus on linguistic, as well as motoric, aspects of speech" (p. 261).

The theoretical rationale for taking a broad-based approach derives from Ingram’s (1989) view of phonology as embracing the study of

- the nature of the underlying representations of speech sounds (or how they are stored in the mind);

- the nature of the phonetic representations (how the sounds are articulated); and

- an organisation level comprising phonological rules or processes that map between the previous two levels.

Consistent with this view of Ingram’s, the current phonological therapy attempts to address the problem of developmental phonological disorders at each of these interdependent levels, with the child as an active participant in the process (Menn, 1976).

Fey's structural plan

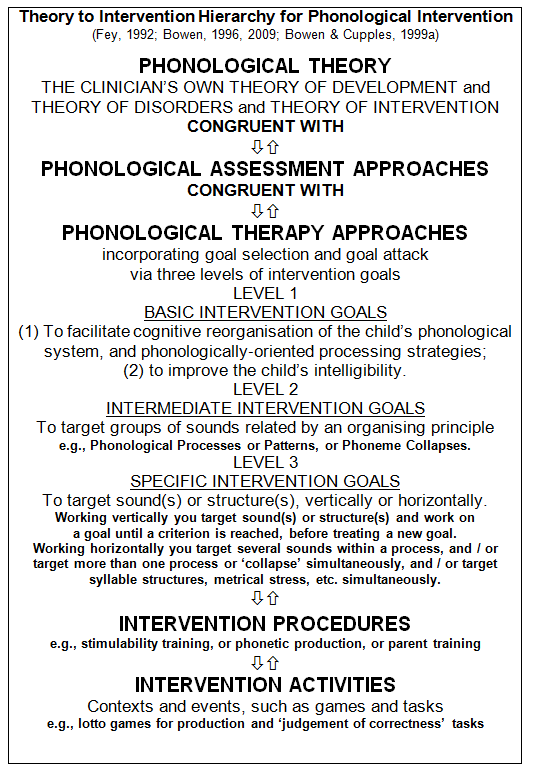

If this sounds complicated, help is at hand thanks to Fey (1992) who developed a structural plan for analysing the form of phonological therapy approaches.

Fey’s framework is useful to the clinical practitioner and/or researcher in three ways. First, it shows the process of converting a phonological theory into a theoretically principled phonological therapy. Second, it illustrates the importance of having a goal setting hierarchy upon which to base treatment decisions and strategies. And third, it captures the clear distinction between intervention approaches, intervention procedures, and intervention activities.

Additionally, it provides a general format upon which case studies can be built, prompting the writer to include a theoretical rationale for assessment and therapy approaches selected, reasons for the basic, intermediate and specific goals targeted, and explanations for the choice of intervention procedures and activities.

Phonological theory

The principles, or theoretical assumptions, upon which any phonological intervention approach is based, derive first from a theory, or theories, of normal phonological development (i.e., how children normally learn the speech sound system). From the practitioner’s beliefs and assumptions about normal development, comes a theory of abnormal phonological development (i.e., a theory of disorders, explaining why some children do not acquire their phonology along typical lines). Then, from the theories of normal and abnormal acquisition, and their formalisms, a theory of intervention can evolve, and, as Ingram (1989) stated, in the case of phonological intervention:

"Therapy will be based on the individual child’s needs, according to the linguistic analysis of his speech and what is known about the process of acquisition" (p. 131).

Theory of development

Phonological acquisition is seen to have four basic, interacting components: auditory perceptual, cognitive, phonological, and neuromotor (Stoel-Gammon & Dunn, 1985). It depends upon the child’s developmental readiness, as well as facilitative psycho-social factors in the communicative milieu.

Theory of disorders

Congruent with this perspective is a theory of phonological disorders as an interruption to normal phonological acquisition, which could have its origins in one or more of the above four components or their environments, thereby adversely affecting the cognitive processes involved in phonological organisation and learning. Gibbon & Grunwell (1990) posited five possible reasons why active phonological learning might slow or stop:

The child may be overwhelmed by the phonetic complexity of the sound patterns he or she is exposed to, and unable to abstract new information from the speech environment.

The child’s maturation may be severely delayed so that for an unduly long period speech production potential is restricted by persisting output constraints.

The child’s phonological organisation may be habituated, so that cognitive flexibility to form new hypotheses is suppressed.

A lack of intrapersonal feedback and awareness may compound these problems.

The presence of variability may suggest an inability to initiate systematic change and regularise the organisation of phonological knowledge.

Theory of intervention

The rationale for the current intervention model involves two aspects. The first aspect is a theoretically based view of phonological acquisition as a complex developmental interaction between motoric, perceptual, conceptual, and cognitive-linguistic capacities and capabilities at the intra-personal level. The second aspect is that the development of such capacities and capabilities is facilitated by interpersonal communication experiences in the child’s particular and immediate linguistic surroundings. With these two aspects in mind, the theoretical position adopted is that a phonological therapy approach aims to facilitate age-appropriate phonological patterns through activities that encourage and nurture the gradual development of the appropriate cognitive organisation of the child’s underlying phonological system.

Assessment

Assessment for the PACT research project

Because the assessments procedures in the research project had to be the same for each child, a standard pre- and post-test battery was selected, comprising:

- Phonological evaluation: (a) oral peripheral examination (Hoffman, Schuckers & Daniloff, 1989); (b) Metaphon Resource Pack Screening Assessment (Dean, Howell, Hill & Waters, 1990), (c) at least the following three procedures of the Phonological Assessment of Child Speech (PACS) (Grunwell, 1985a): the phonetic inventory (the phonetic characteristics of the child’s output phonology), the contrastive assessment (the phonetic and phonological matches and mismatches, and hence the communicative potential of the output phonology), and the developmental assessment (the developmental status of the child’s output phonology);

- Stimulability testing (as described by Stoel-Gammon & Dunn, 1985;

- Structural analysis (with an emphasis on morphology) of a language sample, of no fewer than 200 utterances: Mean Length of Utterance in morphemes (MLUm) was computed using the suggestions provided by Chapman (1981);

- Assessment of receptive vocabulary with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised (Dunn & Dunn, 1981); and,

- Assessment of selected aspects of metalinguistic awareness.

- The pre-test battery also included an audiogram.

Routine clinical assessment and PACT

Unlike the research setting, in the normal clinical routine more flexibility in the choice of assessment tools is possible. For children with moderate to severe intelligibility problems, it is suggested that a screening procedure, which parent(s) can observe, be utilised, in addition to the three PACS procedures (Grunwell, 1985a), or the independent and relational analysis described by Stoel-Gammon & Dunn (1985), or a comparable detailed phonological assessment procedure. It would then be up to the clinician’s judgement as to what additional procedures might be included in the assessment battery.

Therapy

The therapy model, whose development is dynamic and ongoing, emphasises the importance of the child’s active cognitive involvement (Menn, 1976), and family participation (Crago, 1992) in administering its metalinguistic, phonological and phonetic procedures and activities. Since the efficacy study (Bowen, 1996) indicated that the treatment approach was successful, empirically supported guidelines for treating developmental phonological disorders, based on this approach, can be stated as follows:

- Base therapy upon detailed and ongoing phonological assessment in order to target cognitive reorganisation of the underlying system for phoneme use as efficiently and as relevantly as possible for the child at any given time.

- Administer therapy in the form of planned therapy blocks and breaks to allow for the gradual emergence of new phonological patterns.

- Structure therapy sessions so that a 50% exists between auditory and conceptual activities on the one hand, and production activities on the other, thereby acknowledging the important role of listening and thinking in linguistic learning.

- Engage parents and significant others in an active and informed way in the therapeutic process, thus tapping into the resources and capabilities of the most influential people in any child’s early linguistic environment: i.e., his or her family.

- Involve the child as an active participant in therapy, on the basis that language learning is dynamic, interactive and interpersonal, and that the function of phonology is communication.

- Include in the therapy regime these five components: (1) family education; (2) metalinguistic tasks; (3) phonetic production procedures; (4) multiple exemplar techniques; and, (5) homework activities, incorporating (1) to (4) above.

Components of PACT

None of the five components are unique to the model. As a synthesis of several existing approaches, what makes the model different is (1) the style in which children’s families are involved in therapy, (2) the way appointments are scheduled, and (3) the particular combination of the five components to form a total treatment package (Bowen & Cupples, 1999a, 1999b).

Implementation of PACT

More about implementing PACT

Therapy is conducted in a clinical setting by a speech-language pathologist, with active parent participation, and followed up at home by parents, and to a lesser, but none-the-less important extent, at pre-school by early childhood teachers. The following sections detail the aspects of therapy that take place in the three settings.

PACT in the clinic

Therapy sessions occur once weekly (one week apart) at the clinic for periods of approximately ten weeks, alternated with approximately 10-week breaks from therapy attendance. In the third or fourth visit, parents are provided with an informational booklet containing details about developmental phonological disorder and the therapy model. Since the completion of the study in 1996, the booklet has been refined and published (Bowen, 1998a).

Treatment sessions are 50 minutes in length. The child spends 30 to 40 minutes alone with the therapist. The minimum amount of parent participation at the clinic involves the accompanying parent joining the therapist and child for 10 to 20 minutes at the end of a session, or 10 minutes at the beginning and 10 minutes at the end, for the therapist to show the parents what to do for homework. The maximum parent participation entails the parent actively involved in a treatment triad with their child and the therapist, for approximately half of the treatment session (25 minutes).

PACT at home

Homework comprises auditory bombardment, minimal contrast activities, metalinguistic tasks (for example, a judgement of phonological correctness task), and modelling and reinforcement of specified behaviours (for instance, reinforcing the performance of revisions and repairs).

Homework also sometimes includes production practice of 6 to 12 words containing target phonemes. Homework is set out in an exercise book (the speech book) during the session, and parts of therapy sessions, especially segments that demonstrate the performance of metalinguistic tasks, are audiotaped, and sent home for the child and parent/s to listen to as often as they wish.

The suggested duration and frequency of homework is 5 to 7 minutes twice or three times a day, 5 or 6 days a week. The 5 to 6 minute practice sessions can be separated by as little as 5 to 10 minutes.

During the breaks from therapy attendance, parents are asked not to practice for about eight weeks. Two weeks prior to the next treatment block they are asked to read the speech book with the child, and to do any activities the child wishes. In the breaks they are urged to focus on providing to the child modelling corrections, and reinforcement of revisions and repairs.

PACT at pre-school

Preschool teachers are frequently willing and able to give invaluable assistance in implementing the therapy, and general support and encouragement for children and parents. Discussion between the clinician and individual teachers relating to a particular phonologically disabled child, and an arrangement in which speech books are taken to pre-school on a regular basis in order to keep teachers abreast with what is taking place in therapy, can result in teachers making a regular, formal contribution to the therapy process. Teachers are encouraged to reinforce current therapy targets incidentally as opportunities arise, play metalinguistic games, and do homework tasks, for 5 to 7 minutes once a week, if and when they can be incorporated into the pre-school programme. In breaks from therapy attendance the speech book is not taken to pre-school and no formal homework is undertaken there. Teachers are urged, however, to continue to supply to the child modelling corrections, and reinforcement of revisions and repairs.

Intervention procedures

The procedures related to phonological development, and integral to the model, which are considered to be phonological, are: multiple exemplar techniques such as minimal contrast activities (Blache, 1981; Weiner, 1981a) and auditory bombardment (Hodson, 1994), and metalinguistic tasks such as homophony confrontation (Weiner, 1981a), lexical and grammatical innovations (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1980), and phoneme-grapheme correspondence awareness (Allerton, 1976). The procedures related to phonological development, and integral to the model, but not in themselves phonological, are: phonetic production training, the blocks and breaks scheduling of consultations, family participation, and homework.

Intervention activities

Intervention activities for clinic, home and pre-school (or school) will be presented and discussed in the course of the workshop, and are outlined in the workshop notes. A selection of intervention activities is also included in Developmental phonological disorders: A practical guide for families and teachers (Bowen, 1998).

Research background

Treatment efficacy in the area of developmental phonological disorders has predominantly utilised single subject research designs (e.g., Saben & Costello-Ingham, 1991), with a few scattered examples of group designs (e.g., Dean, Donaldson, Grieve, Howell & Reid, 1996).

Bowen’s (1996) efficacy study is in the second category, utilising a longitudinal matched group design. In the study, 14 randomly selected Australian children were treated with the broad-based phonological therapy described above, comprising: family education, metalinguistic tasks, traditional phonetic production procedures, multiple exemplar techniques, and homework, administered in alternating blocks and breaks, each of approximately 10 weeks duration.

The progress of the 14 treated children was compared with that of 8 untreated control children. Analysis of Variance of the initial and probe Severity Ratings of the phonological disabilities, 3 to 11 months apart, showed highly significant selective progress in the treated children only (F(1,20) = 21.22, p = <.01).<.01). Non-significant changes in receptive vocabulary (F< 1) pointed to the specificity of the therapy. The initial severity of the children’s phonological disabilities was the only significant predictor of the duration of therapy they required, with strong correlations between initial severity and number of treatments (r (11)=".75,p=<.01)." A clinically applicable Severity Index with a high correlation (r (79)=".87," p <.01) with the Severity Ratings of experienced speech-language pathologists was developed, and an implementation procedure proposed.

Case studies

Alongside the single-subject and group experimental studies reported in the literature there have been a number of thoughtful and stimulating clinical phonology state of the art papers published in recent years. Notably, articles by Grunwell (1995) and Gierut (1998) have stressed the pedagogic and research value of detailed case studies of individual children’s progress in response to available phonological therapy regimens. There are, of course, many examples of such case descriptions, some dating back to the beginnings of the phonological revolution for example: Blache, Parsons & Humphreys, 1981; and Weiner, 1981(b), and, more recently: Gibbon, Shockey & Reid, 1992; Gierut, 1998; Grunwell, 1989; Grunwell & Russell, 1990; Grunwell, Yavas, Russell & LeMaistre, 1988; Hodson, 1994; Stone & Stoel-Gammon, 1990; and Williams, 1993.

Case studies, detailing phonological treatment approaches, procedures and activities, and the principles and rationales underlying treatment planning decisions, not only provide for the practitioner important information about various options for managing developmental phonological disorders, but also suggest workable formats for clinicians to use in writing up their own work in order to add to the research literature. Accordingly, detailed case studies, the first of which has recently been published (Bowen & Cupples, 1998) were included in the original reporting of the research (Bowen, 1996), exemplifying the therapeutic model in practice.

PACT: Speech Therapy for Josie

References

PACT Publications

Allerton, D. (1976). Early phonotactic development: Some observations on a child’s acquisition of initial consonant clusters. Journal of Child Language, 3, 429 - 433.

Baker, E., van Doorn, J., Reed, V.A. (1996, April). The efficacy of phonological therapy. Paper presented at the Inaugural Conference of the New Zealand Therapists and the Australian Association of Speech and Hearing.

Ball, M. and Kent, R. Eds(1997). The new phonologies: Developments in clinical linguistics. San Deigo: Singular Publishing Group, Inc.

Blache, S.E., Parsons, C., & Humphreys, J.M. (1981). A minimal word-pair model for teaching the linguistic significance of distinctive feature properties. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 291-296.

Bowen, C. (1996). Evaluation of a phonological therapy with treated and untreated groups of young children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Macquarie University.

Bowen, C. (1998a). Developmental phonological disorders: A practical guide for families and teachers. Melbourne: The Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd.

Bowen, C. (1998b). Give me five. A broad-based approach to phonological therapy. Communications Ahead. Dunedin: New Zealand Speech-Language Therapists’ Association Biennial Conference Proceedings.

Bowen, C. & Cupples, L. (1998). A tested phonological therapy in practice. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 14, 1.

Bowen, C. & Cupples, L. (1999a). Parents and children together (PACT): a collaborative approach to phonological therapy. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. Vol 34(1), 35-55.

Bowen, C. & Cupples, L. (1999b). A phonological therapy in depth: a reply to commentaries. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. Vol 34 No 1, 65-83.

Chapman, R.S. (1981). Computing mean length of utterance in morphemes. In Miller, J.F. Assessing language production in children: Experimental procedures. Baltimore: University Park Press.

Chiat, S., & Hunt., J. (1993). Connections between phonology and semantics: an exploration of lexical processing in a language impaired child. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 9, 3.

Crago, M. (1992). Ethnography and language socialization: A cross cultural perspective. Topics in Language Disorders, 12, 28-39.

Dean, E.C., Donaldson, M., Grieve, R., Howell, J., & Reid, J. (1996, April). Evaluating therapy for child phonological disorder. A group study of Metaphon therapy. Paper presented to the Inaugural Conference of the New Zealand College of Speech Therapists and the Australian Association of Speech and Hearing.

Dean, E., Howell, J., Hill, A., & Waters, D. (1990). Metaphon Resource Pack. Windsor, Berks: NFER Nelson.

Dunn, L.M. & Dunn, L.M. (1981). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised. Circle Pines, MN.: American Guidance Service.

Fey, M.E. (1992). Clinical Forum: Phonological assessment and treatment. Articulation and phonology: An addendum. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 277 - 282.

Flynn, L., & Lancaster, G. (1996). Children’s Phonology Sourcebook. Oxford: Winslow Press. Gibbon, F., & Grunwell, P. (1990). Specific developmental language learning disabilities. In P. Grunwell (Ed.). Developmental speech disorders. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone.

Gibbon, F., Shockey, L., & Reid, J. (1992). Description and treatment of abnormal vowels in a phonologically disordered child. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 8, 30-59.

Gierut, J.A. (1992). The conditions and course of induced phonological change.Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 1049-1063.

Gierut, J.A. (1998). Treatment efficacy: Functional phonological disorders in children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 41, S85-S100.

Grunwell, P. (1985a). Phonological Assessment of Child Speech (PACS). Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

Grunwell, P. (1985b). Developing phonological skills. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 1, 65-72.

Grunwell, P. (1988). Comment on ‘Helping the development of consonant contrasts’. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 4, 57-59.

Grunwell, P. (1989). Developmental phonological disorders and normal speech development: A review and illustration. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 5, 304-319.

Grunwell, P. (1995). Changing phonological patterns. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 11, 61-78.

Grunwell, P., & Russell, J. (1990). A phonological disorder in an English-speaking child: A case study. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 4, 29-38.

Grunwell, P., Yavas, M., Russell, J., & LeMaistre, M. (1988). Developing a phonological system: A case study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 4, 142-153.

Hodson, B. (1994). Determining phonological intervention priorities: Expediting intelligibility gains. In Williams, E.J. and Langsam, J., editors. Children’s phonology disorders: Pathways and patterns. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Hoffman, P.R., Schuckers, G.H., & Daniloff, R.G. (1989). Children’s phonetic disorders: Theory and treatment. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. 203 -206.

Ingram, D. (1976). Phonological disability in children. London: Edward Arnold.

Ingram, D. (1989). Phonological disability in children.(2nd ed.). London: Cole & Whurr, Ltd.

Kamhi, A.G. (1992). Clinical forum: Phonological assessment and treatment. The need for a broad-based model of phonological disorders. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 261-268.

Locke, J. (1994) Developmental paths to phonology. In Williams, E.J. and Langsam, J., editors. Children’s phonology disorders: Pathways and patterns. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

McWilliams, P.J., Winton, P.J., & Crais, E.R. (1996). Practical Strategies for Family-Centered Early Intervention. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group, Inc.

Menn, L. (1976). Evidence for an interactionist discovery theory of child phonology. Papers and Reports on Language Development, 12, 169-177. Stanford: Stanford University.

Pollock, K.E. (1994) Overview: Children’s phonological disorders. In Williams, E.J. and Langsam, J., editors. Children’s phonology disorders: Pathways and patterns. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Saben, C., & Costello Ingham, J. (1991). The effects of minimal pairs treatment on the speech-sound production of two children with phonologic disorders. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 1023-1040.

Schriberg, L.D., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1980). Natural Process Analysis. New York: Academic Press.

Sommers, R.K., Logsdon, B. & Wright, J. (1992). A review and critical analysis of treatment research related to articulation and phonological disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 25, 3-22.

Stackhouse, J., & Wells, B. (1993). Psycholinguistic assessment of developmental speech disorders.European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 28, 349-367.

Stoel-Gammon, C., & Dunn, C. (1985). Normal and abnormal phonology in children. Austin Texas: Pro-Ed. Inc.

Stampe, D. (1979). A dissertation on natural phonology. New York; Academic Press.

Stone, J.R., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (1990). One class at a time: A case study of phonological learning. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 6, 173-191.

Vihman, M.M. (1996). Phonological development: The origins of child language. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Weiner, F. (1981a). Treatment of phonological disability using the method of meaningful contrast: Two case studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 97-103.

Weiner, F. (1981b). Systematic sound preference as a characteristic of phonological disability. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 281-286.

Williams, A. L. (1993). Phonological reorganization: A qualitative measure of phonological improvement. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 2, 44-51.